Fiche du document numéro 24330

Num

24330

Date

Thursday May 01, 2014

Amj

Auteur

Taille

181358

Pages

3

Titre

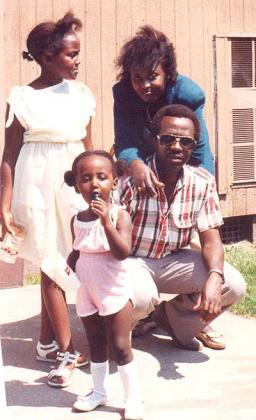

JB Habyarimana, the Butare prefect who bravely resisted the Genocide

Sous titre

He is described as a feisty man who always put a smile on people’s face, but, most importantly, as a brilliant leader who fought, body and soul, for the people he led until he was killed.

Source

Type

Article de journal

Langue

EN

Citation

Jean-Baptiste Habyarimana, who was the préfet (governor) of Butare prefecture, is hailed as someone who opposed the killings in his area and offered protection to thousands of Tutsi in 1994. When mass killings erupted across the country after the death of then president Juvénal Habyarimana on the night of April 6, 1994, Butare prefecture remained relatively calm. News that the south-central prefecture was safe spread like bushfire, leading to thousands of fleeing Tutsi from other areas to throng Butare in the days that followed the outbreak of the killings. Testimonies indicate that Préfet Habyarimana, one of the rare Tutsi to hold such a position at the time and a man who actively opposed the Genocide, was the face behind the seeming calm. His dismissal in mid-April and his subsequent detention and later murder paved way for the genocidal regime to execute its plan, leaving thousands of Tutsi in his prefecture killed in just a matter of days.

‘Sacré’

Prefect Habyarimana’s long-time friends, including those he went to school with and who knew him when he was the leader of Butare, describe him as a bright leader, a humorous man, a warm gentleman and someone who always knew how to reassure those who needed his support. Innocent Kayitare, 61, a man who knew him at the former National University of Rwanda, while both were students there, says Habyarimana was better known at the campus by the nickname ‘Sacré’ (Sacred). “He was always smiling; in a jovial mood,” Kayitare says. “He avoided anything that could cause conflict between him and others.”

Laurent Gatera, 59, also speaks of him as being “very bright.” After completing his studies at the National University of Rwanda (now University of Rwanda’s College of Arts and Humanities), in the late 1970s, Habyarimana was sent to the US and returned in the mid-1980s after completing his doctoral studies. Upon his return, Habyarimana, a native of the former Runyinya commune now in Huye District, became a lecturer in the Department of Civil Engineering at the Huye-based university until he was named Prefet around 1992.

Lambert Byemayire, one of his civil engineering students and a friend of the Habyarimana family, says the academic-turned-politician “exuded love for humanity and fought for the truth in every situation.” “He was a real man,” he says.

Standing against the Genocide

In October 1990, Habyarimana, who was then a lecturer, was arrested alongside other elite Tutsi in Butare on accusations that they were accomplices of the Rwanda Patriotic Army, which had then launched a military campaign against the genocidal government of Juvenal Habyarimana. They were detained for about six months at Karubanda Prison. Gatera, who was with Jean-Baptiste Habyarimana and other detainees at the prison, says they were tortured by the regime’s operatives. “But JB Habyarimana didn’t lose hope. He kept comforting and reassuring us,” Gatera says. They were released in March 1991, following the ratification of N’sele Ceasefire Agreement that was signed between the then government of Rwanda and the Rwanda Patriotic Front, the political wing of RPA. The accords, which were signed on March 29, 1991, in DR Congo, then Zaire, provided for the cessation of hostilities and the release of political prisoners.

Around 1992, the government was forced to open up the political space to allow multiparty system, which saw the creation of many political parties opposed to the then ruling party, the Mouvement Républicain National pour la Démocratie et le Dévelopement (MRND). JB Habyarimana joined the Liberal Party (PL), marking his entry into politics. Then in a surprise move, he was later appointed the Butare governor on the PL ticket and ruled Butare prefecture until his dismissal in April 1994.

Described as a ‘rebel province’, Butare was the only prefecture that remained untouched when the country erupted into bloodshed in early April 1994. The calm lasted for about two weeks. Yet Butare is among the areas that lost the most lives during the Genocide. Some estimates claim that more than 20 per cent of the more than a million Tutsi killed during the Genocide died in Butare alone. In her book, Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide, Linda Melvern says that as killings intensified in Gikongoro, Kigali and Gitarama, and as many Tutsi continued to arrive in Butare seeking protection, Habyarimana ordered that meetings be held to try to stop the violence.

Arrest and murder

Habyarimana attended some of the meetings and urged people to refrain from getting involved in the killings, testimonies gathered by The New Times show. Unfortunately, in a broadcast on April 17, Radio Television Libre des Milles Collines (RTLM) accused him of being an agent of RPA and the following day he was removed from his position. On April 19, interim president Théodore Sindikubwabo arrived in Butare where he attended a ceremony to appoint a new leader for Butare. Habyarimana was then officially branded as an enemy of the State. It is at the same ceremony that Sindikubwabo allegedly delivered his infamous speech condemning in the strongest terms those who were not “working” (read killing Tutsi) and instructed them to “get out of the way and let us work.”

In the following days, Habyarimana was arrested, and transferred to Gitarama where the Sindikubwabo government was based. It is alleged that once there he was tortured before being killed. To-date, his remains are yet to be recovered. Habyarimana’s wife and two children were, on their parts, killed at their home near Butare aerodrome, according to witnesses. Those who visited Habyarimana’s home shortly after the Genocide say its walls were blood-stained and suspect his two daughters were smashed against the walls by their murderers. “His memory lives on forever and his legacy will always inspire us,” Gatera says.